Introduction

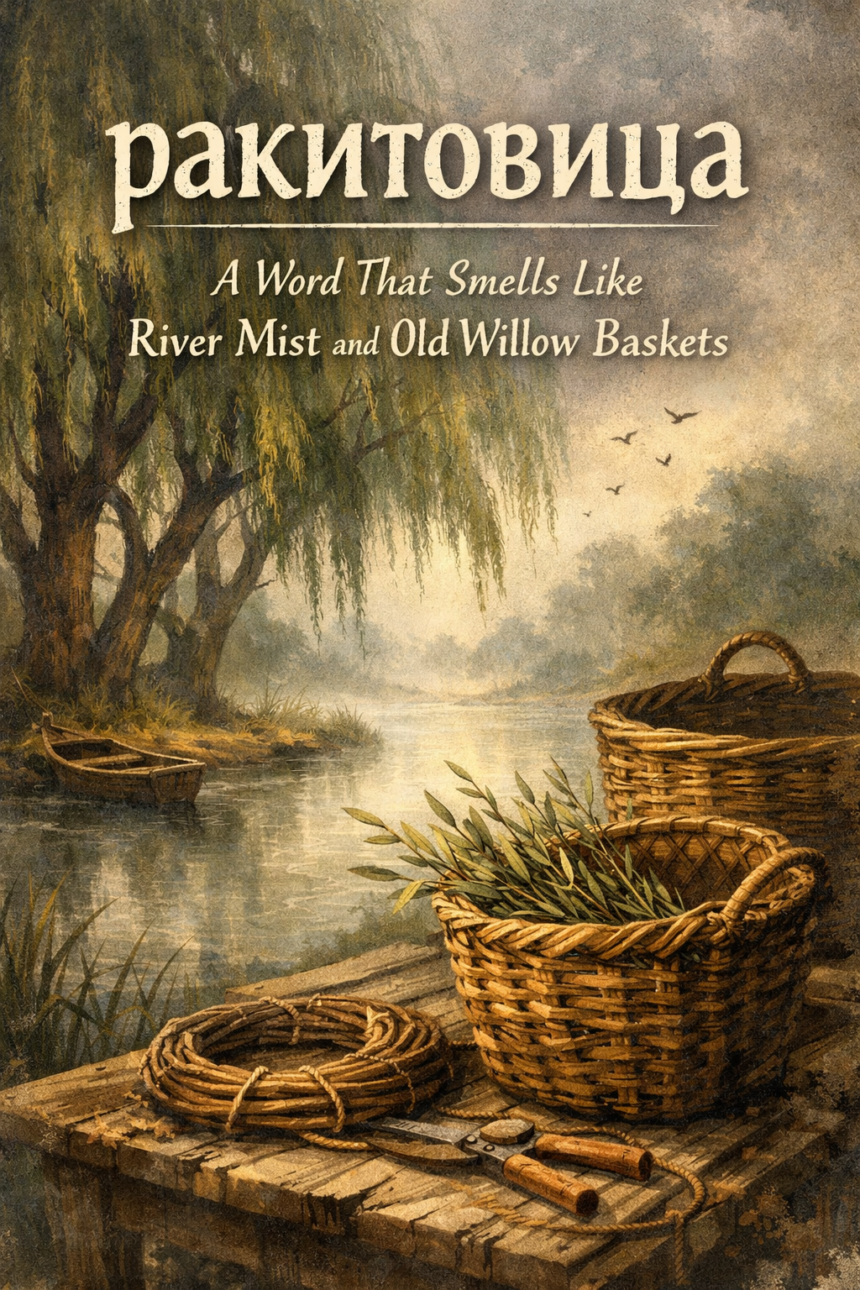

Pакитовица Some words don’t just mean something… they feel like something. You say them out loud and—boom—your brain paints a scene without asking permission. A chilly riverbank. Soft mud under boots. A line of willows leaning over water like they’re gossiping. A small road going nowhere fast. A dog barking once, just to prove it’s still on duty.

- Introduction

- How a Place-Name Can Start With a Tree (Yep, Really)

- Why Willows Keep Winning the Naming Contest

- ракитовица as a “Map Word” (A Clue Hiding in Plain Sight)

- The Tiny Villages We Don’t Talk About Enough

- A Quick “Word Traveler’s” Guide: How to Explore a Name Like This

- The Internet’s Favorite Problem: One Word, Too Many Meanings

- The “Willow Logic” of Everyday Life

- What This Word Teaches Us (Without Turning Into a Lecture)

- FAQs

- 1) Is this word only a place-name?

- 2) What’s the connection to willows?

- 3) Is there an actual village with a similar name?

- 4) Why do Slavic regions name places after plants?

- 5) How should I research a word like this without getting confused?

- Conclusion

That’s the vibe I get from this word, and I’m not alone. Across Slavic-speaking landscapes, names often grow straight out of nature: trees, rivers, reeds, hills. And when you bump into a word that carries a plant inside it, it’s usually not an accident. It’s a hint. A little “psst… look around.”

So let’s treat this like a mini adventure—part language story, part imagination, part “wait, what does this word really point to?” Along the way, we’ll talk about how place-names are born, why willows keep showing up in them, and why a single word can make you feel like you’ve stepped into a quieter, slower world.

How a Place-Name Can Start With a Tree (Yep, Really)

Here’s the thing: before maps were crisp and governments were neat, people named places the practical way.

-

“Where are you from?”

-

“From the place with the willows.”

-

“Oh, you mean that place.”

And that’s how it sticks.

In Slavic languages, a lot of names come from natural markers—especially trees. One root that shows up is connected to basket willow, the kind of willow used for weaving and wickerwork. Wiktionary even defines the Russian word ракита as “basket willow” and also the branches/wood used for weaving.

Pакитовица So when you see a name built from that root, it’s not hard to guess the original picture: willow thickets, flexible branches, and people making practical stuff out of whatever grew nearby. Simple life, clever hands.

And honestly? That’s kind of beautiful.

Why Willows Keep Winning the Naming Contest

Willows are drama queens—in a good way. They don’t grow just anywhere. They like water. They like edges: riverbanks, marshes, damp soil, Pакитовица places where land and water keep negotiating. That makes them perfect landmarks.

Willows also matter to everyday life:

-

They’re easy to spot from far away (that shape! that lean!)

-

Their branches are flexible and useful (baskets, fences, ties)

-

They thrive where farming communities often settle (water nearby is life)

So, naturally, a willow-heavy area becomes a “willow place,” and a “willow place” becomes a name people pass down like a family recipe.

ракитовица as a “Map Word” (A Clue Hiding in Plain Sight)

If you love language, this is the fun part.

Many Slavic place-names work like little puzzles: root + suffix = meaning-ish. The root points to a feature (like willow), and the suffix often signals place or area. It’s like the name is saying: “This is the spot where that thing happens.”

And while different languages handle suffixes differently, that overall pattern—nature + location—shows up all over the region.

To make it concrete, there’s a real village in Croatia called Rakitovica, listed as a settlement in the Donji Miholjac area, with recent population figures noted by Wikipedia. It’s also documented in Wikimedia Commons as a village in Osijek-Baranja County.

Now, I’m not saying one single village “explains” the whole word. But it does prove something important: this name exists in real geography, not just in poetic daydreams.

The Tiny Villages We Don’t Talk About Enough

Big cities get all the spotlight. Meanwhile, small villages—quiet, stubborn, alive in their own way—keep the cultural engine running.

And small places do this funny thing: they make time feel different.

In a city, time is a shove. In a rural place, time is a sigh.

You’ll notice details you usually bulldoze past:

-

the way smoke curls from a chimney like it’s drawing lazy commas in the air

-

the sound of a bicycle chain in the distance

-

the silence between two birds calling back and forth

-

the fact that nobody’s in a hurry… and somehow nothing collapses because of it

It’s not “better” or “worse.” It’s just… slower. And after a while, slow starts to feel like a superpower.

A Quick “Word Traveler’s” Guide: How to Explore a Name Like This

If you ever run into an unfamiliar place-name (or a word that smells like geography), here’s a simple way to explore it without turning it into homework.

-

Say it out loud.

Rhythm matters. Your mouth can tell you what your brain can’t yet. -

Look for the root.

Is there a plant, animal, river, color, or shape hiding in there? -

Ask: what would this land look like?

Muddy? Rocky? Forested? Windy? Names often describe terrain. -

Check if it’s also a surname or nickname.

In many cultures, places and families trade names back and forth. -

Don’t panic if sources disagree.

The internet loves a messy story. Names can be used in multiple ways across regions.

Speaking of that last point…

The Internet’s Favorite Problem: One Word, Too Many Meanings

Pакитовица If you search this word online, you’ll probably stumble into a weird crossroads: some pages talk about it like it’s linked to a plant or berry (and you might see claims about sea buckthorn and “superfood” stuff). Other pages talk about it like it’s a place-name.

What’s going on?

A few possibilities, and none of them are shocking:

-

Different regions use similar-sounding names for different things

-

Transliteration (Cyrillic ↔ Latin) creates spelling cousins

-

Content farms remix meanings to sound “educational”

-

Folk naming traditions overlap (plants become places, places become product names)

So instead of forcing one strict definition, it’s often smarter to treat the word as a cultural signpost: it points you toward a landscape where nature matters enough to name the land after it.

And honestly, that’s the part worth keeping.

The “Willow Logic” of Everyday Life

Let’s zoom out for a second.

A willow isn’t just a tree.Pакитовица In a lot of Slavic and Eastern European storytelling, it’s a symbol—quiet, bending, surviving. It doesn’t snap in the wind; it negotiates with it. That’s not weakness. That’s strategy.

So when a place-name carries willow-energy, it can hint at a local identity too:

-

patient

-

practical

-

close to water and soil

-

skilled with hands

-

not interested in showing off

It’s the opposite of flashy. More like: “We’ve been here. We’ll stay here. You want tea or not?”

What This Word Teaches Us (Without Turning Into a Lecture)

Alright, I’ll keep it real. This isn’t just about one term. It’s about what names do to us.

A name can:

-

store history without writing it down

-

preserve ecology (even when the ecology changes later)

-

tell you what mattered to the people who settled there

-

create a mood before you arrive

And when you start noticing this, travel changes. Even reading changes. You stop skimming place-names like they’re random labels and start treating them like tiny stories pinned to the map.

Dangling off the edge of meaning, you realize something kind of wild: language is a landscape, too.

FAQs

1) Is this word only a place-name?

Pакитовица Not necessarily. In Slavic naming traditions, words can overlap between geography, local nicknames, and nature-based terms. Context is everything—where you saw it, how it was written, and what language community is using it.

2) What’s the connection to willows?

The root connected to ракита is associated with “basket willow,” which is traditionally used for weaving and wickerwork.

3) Is there an actual village with a similar name?

Yes. For example, Rakitovica is documented as a village in Croatia (including administrative and population details).

4) Why do Slavic regions name places after plants?

Because plants are reliable landmarks and practical resources. Before modern mapping, describing the land was the easiest way to identify it—and the most useful way to remember it.

5) How should I research a word like this without getting confused?

Use a “two-lens” approach: (1) check a solid language source (like a dictionary or etymology reference), and (2) check a solid geography source (like an encyclopedia entry or official data site). When they don’t match perfectly, don’t panic—names travel.

Conclusion

Pакитовица So what do we do with a word like this?

We don’t cage it. We walk with it.

A name like ракитовица doesn’t have to be one rigid thing to be meaningful. It can be a linguistic breadcrumb and a mood all at once: a hint of willow branches, river edges, and settlements that grew where the land made sense. And in a world that loves noise, that quiet rootedness feels almost rebellious—like a whispered reminder that not everything worth knowing is trending.